Processes and model formulation

Domain and definitions

Coordinate system

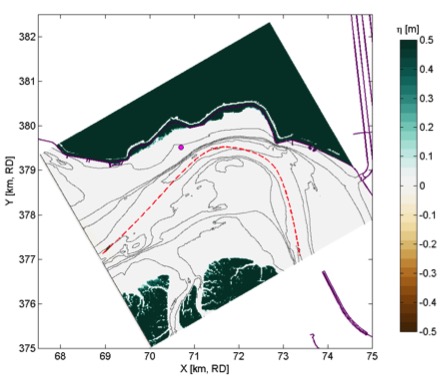

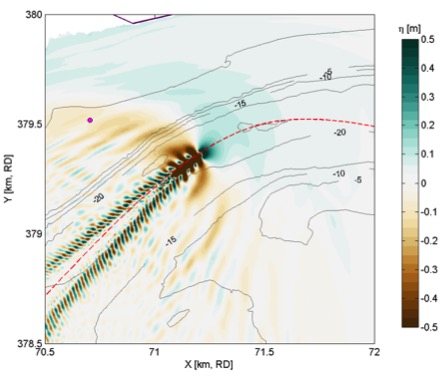

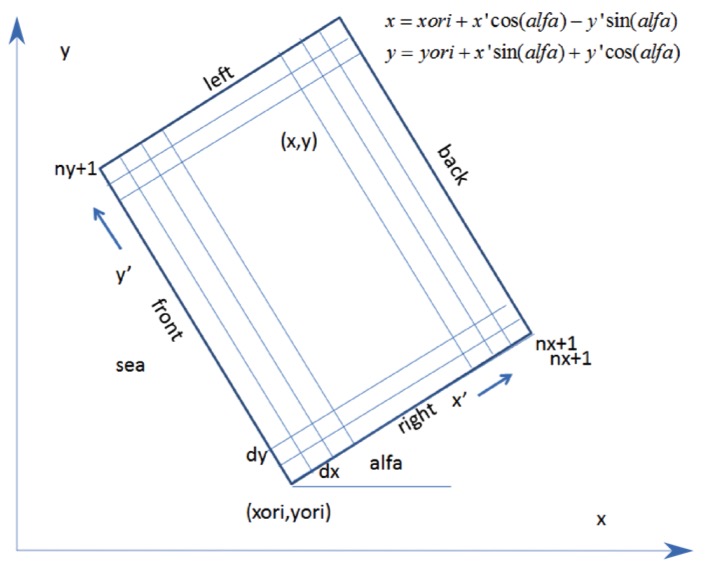

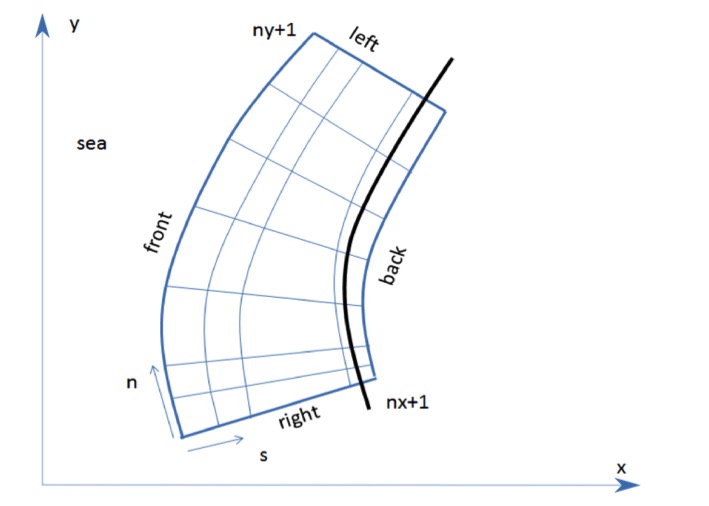

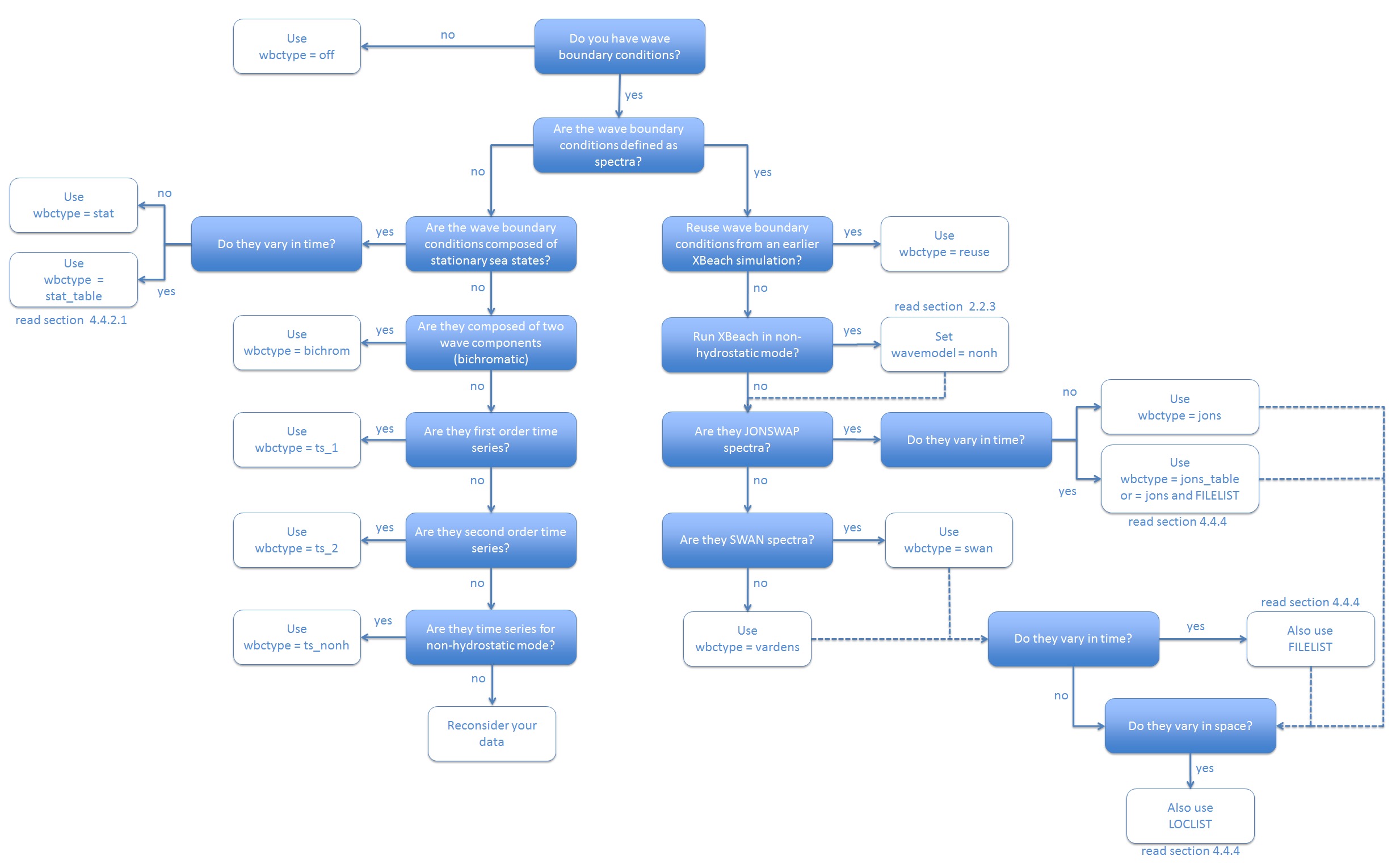

XBeach uses a coordinate system where the computational x-axis is always oriented towards the coast, approximately perpendicular to the coastline, and the y-axis is alongshore, see Fig. 1 and Fig. 2. This coordinate system is defined in world coordinates. The grid size in x- and y-direction may be variable but the grid must be curvilinear. Alternatively, in case of a rectangular grid (a special case of a curvilinear grid) the user can provide coordinates in a local coordinate system that is oriented with respect to world coordinates (xw, yw) through an origin (xori, yori) and an orientation (alfa) as depicted in Fig. 1. The orientation is defined counter-clockwise w.r.t. the xw-axis (East).

Fig. 1 Rectangular coordinate system of XBeach

Grid set-up

The grid applied is a staggered grid, where the bed levels, water levels, water depths and concentrations are defined in cell centers, and velocities and sediment transports are defined in u- and v-points, viz. at the cell interfaces. In the wave energy balance, the energy, roller energy and radiation stress are defined at the cell centers, whereas the radiation stress gradients are defined at u- and v-points.

Velocities at the u- and v-points are denoted by the output variables uu and vv respectively; velocities u and v at the cell centers are obtained by interpolation and are for output purpose only. The water level, zs, and the bed level, zb, are both defined positive upward. uv and vu are the u-velocity at the v-grid point and the v-velocity at the u-grid point respectively. These are obtained by interpolation of the values of the velocities at the four surrounding grid points.

The model solves coupled 2D horizontal equations for wave propagation, flow, sediment transport and bottom changes, for varying (spectral) wave and flow boundary conditions.

Fig. 2 Curvilinear coordinate system of XBeach

Hydrodynamics options

XBeach was originally developed as a short-wave averaged but wave-group resolving model, allowing resolving the short wave variations on the wave group scale and the long waves associated with them. Since the original paper by Roelvink et al. [2009] a number of additional model options have been implemented, thereby allowing users to choose which time-scales to resolve:

Stationary wave model (keyword: wavemodel = stationary), efficiently solving wave-averaged equations but neglecting infragravity waves;

Surfbeat mode (instationary) (keyword: wavemodel = surfbeat), where the short wave variations on the wave group scale (short wave envelope) and the long waves associated with them are resolved;

Non-hydrostatic mode (wave-resolving) (keyword: wavemodel = nonh), where a combination of the non-linear shallow water equations with a pressure correction term is applied, allowing to model the propagation and decay of individual waves.

In the following these options are discussed in more detail. Important to note that all times in XBeach are prescribed on input in morphological time. If you apply a morphological acceleration factor (keyword: morfac) all input time series and other time parameters are divided internally by morfac. This way, you can specify the time series as real times, and vary the morfac without changing the rest of the input files (keyword: morfacopt = 1).

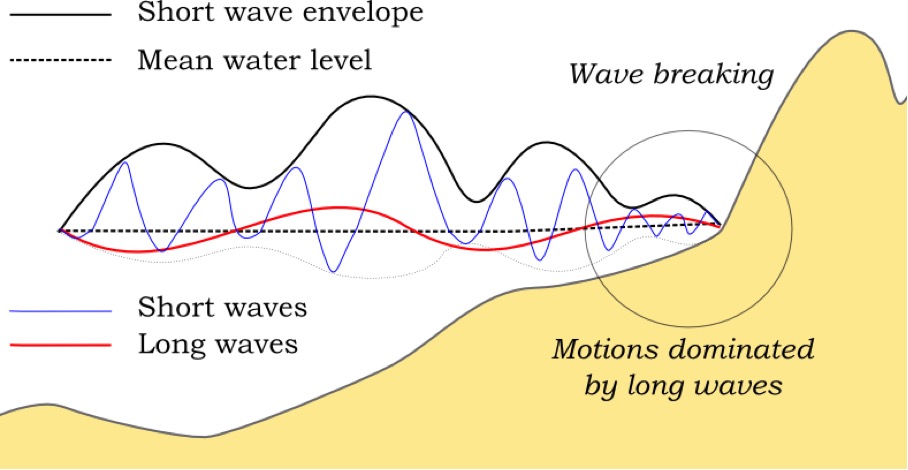

Fig. 3 Principle sketch of the relevant wave processes

Stationary mode

See also

The stationary mode is implemented in mod:wave_stationary_module.

In stationary mode the wave-group variations and thereby all infragravity motions are neglected. This is useful for conditions where the incident waves are relatively small and/or short, and these motions would be small anyway. The model equations are similar to HISWA ([Holthuijsen et al., 1989]) but do not include wave growth or wave period variations. Processes that are resolved are wave propagation, directional spreading, shoaling, refraction, bottom dissipation and wave breaking, and a roller model is included; these processes are usually dominant in nearshore areas of limited extent. For the breaking dissipation we use the Baldock et al. [1998] model, which is valid for wave-averaged modeling. The radiation stress gradients from the wave and roller model force the shallow water equations, drive currents and lead to wave setdown and setup. Additionally, wind and tidal forcing can be applied.

The mean return flow due to mass flux and roller is included in the model and affects the sediment transport, leading to an offshore contribution. To balance this, effects of wave asymmetry and skewness are included as well. Bed slope effects can further modify the cross-shore behavior. A limited number of model coefficients allow the user to calibrate the profile shape resulting from these interactions.

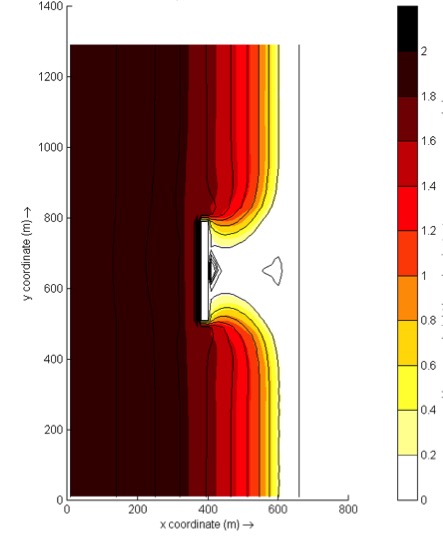

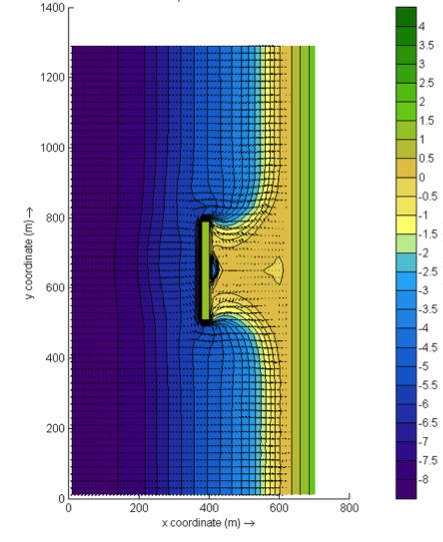

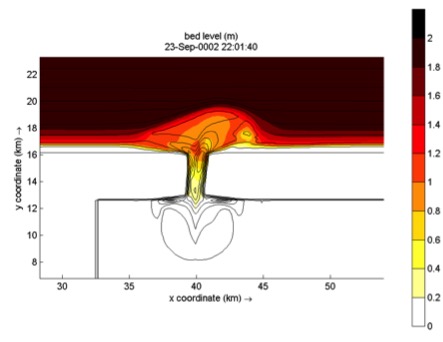

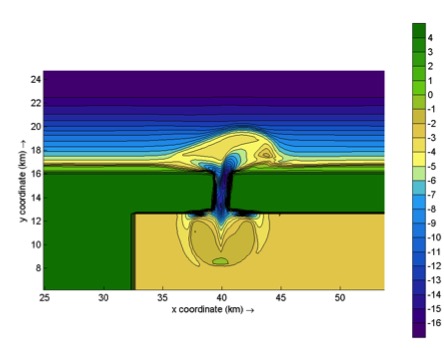

A typical application would be to model morphological changes during moderate wave conditions, often in combination with tides. The wave boundary conditions can be specified as constant (keyword: wbctype = params) or as a time-series of wave conditions (keyword: wbctype = jonstable). Typical examples of such model applications are given below for tombolo formation behind an offshore breakwater (left panel) and development of an ebb delta at a tidal inlet (right panel). A big advantage of the stationary XBeach wave model over other models is that the lateral boundaries are entirely without disturbance if the coast is longshore uniform near these boundaries.

Surf beat mode (instationary)

See also

The surfbeat mode is implemented in mod:wave_instationary_module.

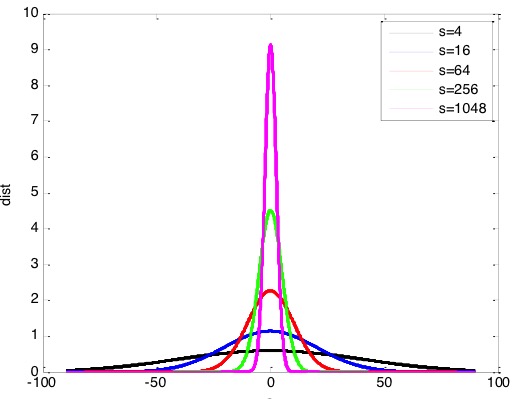

The short-wave motion is solved using the wave action equation which is a time-dependent forcing of the HISWA equations [Holthuijsen et al., 1989]. This equation solves the variation of short-waves envelope (wave height) on the scale of wave groups. It employs a dissipation model for use with wave groups [Daly et al., 2012, Roelvink, 1993] and a roller model [Nairn et al., 1990, Stive and De Vriend, 1994, Svendsen, 1984] to represent momentum stored at the surface after breaking. These variations, through radiation stress gradients [Longuet-Higgins and Stewart, 1962, Longuet-Higgins and Stewart, 1964] exert a force on the water column and drive longer period waves (infragravity waves) and unsteady currents, which are solved by the nonlinear shallow water equations [Phillips, 1977]. Thus, wave-driven currents (longshore current, rip currents and undertow), and wind-driven currents (stationary and uniform) for local wind set-up, long (infragravity) waves, and runup and rundown of long waves (swash) are included.

Using the surfbeat mode is necessary when the focus is on swash zone processes rather than time-averaged currents and setup. It is fully valid on dissipative beaches, where the short waves are mostly dissipated by the time they are near the shoreline. On intermediate beaches and during extreme events the swash motions are still predominantly in the infragravity band and so is the runup.

Under this surfbeat mode, several options are available, depending on the circumstances:

1D cross-shore; in this case the longshore gradients are ignored and the domain reduces to a single gridline (keyword: ny = 0). Within this mode the following options are available:

Retaining directional spreading (keyword: dtheta < thetamax - thetamin); this has a limited effect on the wave heights because of refraction, but can also allow obliquely incident waves and the resulting longshore currents;

Using a single directional bin (keyword: dtheta = thetamax- thetamin); this leads to perpendicular waves always and ignores refraction. If the keyword snells = 1 is applied, the mean wave direction is determined based on Snells law. In this case also longshore currents are generated.

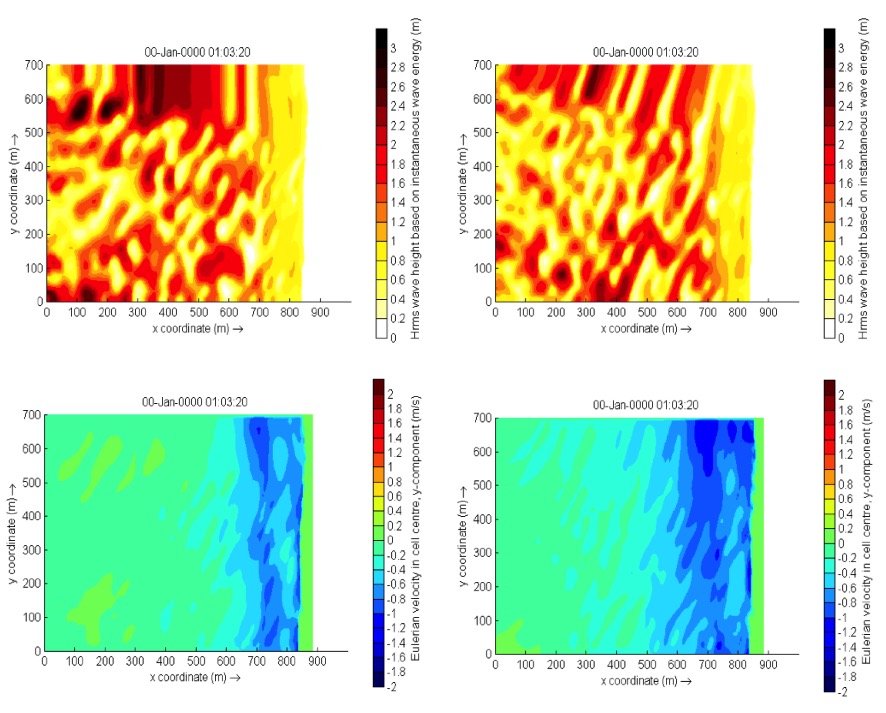

2DH area; the model is solved on a curvilinear staggered grid (rectilinear is a special case). The incoming short wave energy will vary along the seaward boundary and in time, depending on the wave boundary conditions. This variation is propagated into the model domain. Within this mode the following options are available:

Resolving the wave refraction ‘on the fly’ using the propagation in wave directional space. For large directional spreading or long distances this can lead to some smoothing of groupiness since the waves from different directions do not interfere but their energy is summed up. This option is possible for arbitrary bathymetry and any wave direction. The user must specify the width of the directional bins for the surfbeat mode (keyword: dtheta)

Solving the wave direction at regular intervals using the stationary solver, and then propagating the wave energy along the mean wave direction. This preserves the groupiness of the waves therefore leads to more forcing of the infragravity waves (keyword: single_dir = 1). The user must now specify a single directional bin for the instationary mode (dtheta = thetamax - thetamin) and a smaller bin size for the stationary solver (keyword: dtheta_s).

For schematic, longshore uniform cases the mean wave direction can also be computed using Snells law (keyword: snells = 1). This will then give comparable results to the single_dir option.

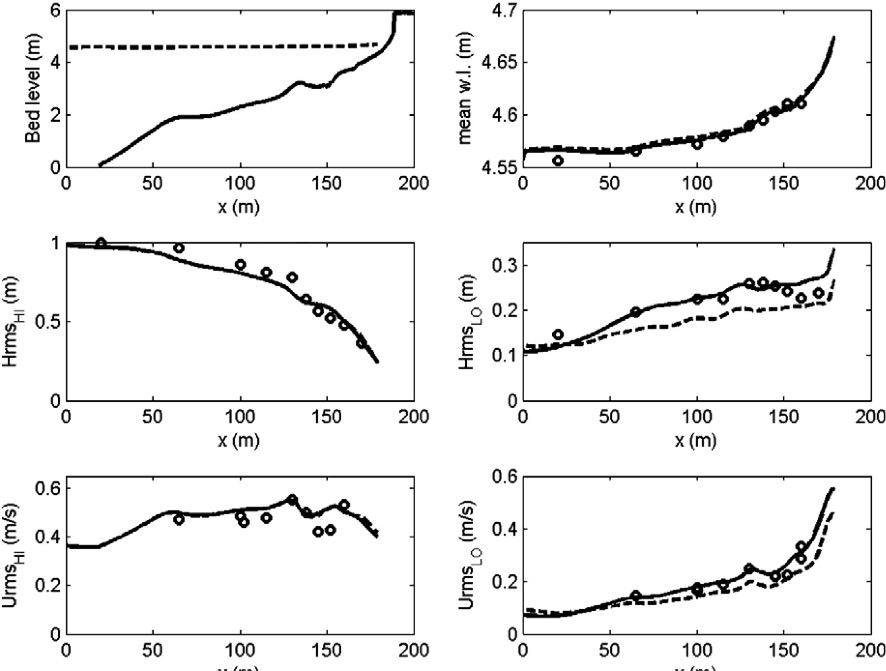

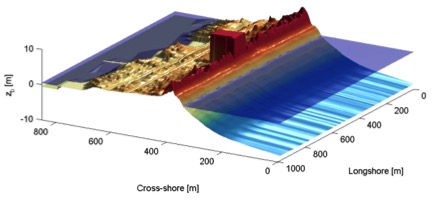

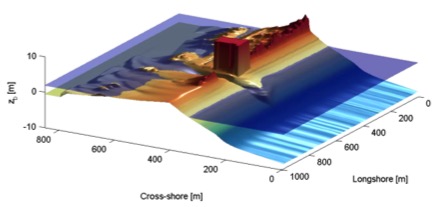

In the figures below some typical applications of 1D and 2D models are shown; a reproduction of a large-scale flume test, showing the ability of XBeach to model both short-wave (HF) and long-wave (LF) wave heights and velocities; and a recent 2DH simulation [Nederhoff et al., 2015] of the impact of hurricane Sandy on Camp Osborne, Brick, NJ.

Fig. 4 Computed and observed hydrodynamic parameters for test 2E of the LIP11D experiment. Top left: bed level and mean water level. Top right: measured (dots) and computed as simulated by XBeach

Pre (left) and post-Sandy (right) in a three dimensional plot with both bed and water levels as simulated by XBeach ([Nederhoff et al., 2015])

Non-hydrostatic mode (wave resolving)

See also

The non-hydrostatic mode is implemented in mod:nonh_module.

For non-hydrostatic XBeach calculations (keyword: wavemodel = nonh) depth-averaged flow due to waves and currents are computed using the non-linear shallow water equations, including a non-hydrostatic pressure. The depth-averaged normalized dynamic pressure (\(q\)) is derived in a method similar to a one-layer version of the SWASH model [Zijlema et al., 2011]. The depth averaged dynamic pressure is computed from the mean of the dynamic pressure at the surface and at the bed by assuming the dynamic pressure at the surface to be zero and a linear change over depth.

Under these formulations dispersive behavior is added to the long wave equations and the model can be used as a short-wave resolving model. Wave breaking is implemented by disabling the non-hydrostatic pressure term when waves exceed a certain steepness, after which the bore-like breaking implicit in the momentum-conserving shallow water equations takes over.

In case the non-hydrostatic mode is used, the short wave action balance is no longer required. This saves computation time. However, in the wave-resolving mode we need much higher spatial resolution and associated smaller time steps, making this mode much more computationally expensive than the surfbeat mode.

The main advantages of the non-hydrostatic mode are that the incident-band (short wave) runup and overwashing are included, which is especially important on steep slopes such as gravel beaches. Another advantage is that the wave asymmetry and skewness are resolved by the model and no approximate local model or empirical formulation is required for these terms. Finally, in cases where diffraction is a dominant process, wave-resolving modeling is needed as it is neglected in the short wave averaged mode. The XBeach-G formulations for gravel beaches [McCall et al., 2014] are based on the non-hydrostatic mode. Although sandy morphology can be simulated using the wave-resolving mode, it has not been extensively validated and it is likely that changes in the sediment transport formulations will be implemented in the near future.

To improve the dispersive behaviour a (reduced) 2-layer non-hydrostatic is implemented as well [de Ridder et al., 2021]. In this version (keyword: nhq3d = 1, see Section Reduced two layer model (nh+)), the pressure in the vertical is described by a hydrostatic pressure assumption in the bottom layer, and a non-hydrostatic distribution in the upper layer.

An interesting recent application that has been validated for a number of cases concerns the modeling of primary waves generated by large ships, see Ship-induced wave motions.

Fig. 5 Measured (black) and modeled (red) time series of overtopping during BARDEX experiment, from [McCall et al., 2014].

Short wave action

Short wave action balance

See also

The short wave action balance is implemented in func:wave_instationary_module/wave_instationary.

The wave forcing in the shallow water momentum equation is obtained from a time dependent version of the wave action balance equation. Similar to Delft University (stationary) HISWA model ([Holthuijsen et al., 1989]) the directional distribution of the action density is taken into account, whereas the frequency spectrum is represented by a frequency, best represented by the spectral parameter \({f}_{m-1,0}\). The wave action balance (keyword: swave) is then given by:

In which the wave action \(A\) is calculated as:

where \(\theta\) represents the angle of incidence with respect to the x-axis, \({S}_{w}\) represents the wave energy density in each directional bin and \(\sigma\) the intrinsic wave frequency. The intrinsic frequency \(\sigma\) and group velocity \({c}_{g}\) is obtained from the linear dispersion relation. The intrinsic frequency is for example obtained with:

The wave action propagation speeds in \(x\), \(y\) and directional space are given by:

where \(h\) represents the local water depth and \(k\) the wave number. The intrinsic wave frequency \(\sigma\) is determined without wave current interaction (keyword: wci = 1, see Section 2.3.1.1), which means it is equal to the absolute radial frequency \(\omega\).

Wave-current interaction (wci)

See also

The wave-current interaction is implemented in func:wave_instationary_module/wave_instationary.

Wave-current interaction is the interaction between waves and the mean flow. The interaction implies an exchange of energy, so after the start of the interaction both the waves and the mean flow are affected by each other. This feature is especially of importance in gullies and rip-currents ([Reniers et al., 2007]).

In XBeach this is taken into account by correcting the wave number \(k\) with the use of Eikonal equations, which will have impact on the group and wave propagation speed (x, y, and directional space). The cross-shore and alongshore wave numbers, \({k}_{x}\) and \({k}_{y}\), are defined according to equation (5). In these formulations the subscripts refer to the direction of the wave vector components.

Where subscript \(n-1\) refers the wave number of the previous time step, \(k_{x}^{:}\) and \(k_{y}^{:}\) are the wave number corrections and \({k}_{x}\) and \({k}_{y}\) are the corrected wave numbers that take into account the presence of a current. The correction terms are determined with a second set of equations, the Eikonal equations:

The wave number is then given by:

The absolute radial frequency \(\omega\) is calculated with:

where \({u}^{L}\) and \({v}^{L}\) are the cross-shore and alongshore depth-averaged Lagrangian velocities respectively. The wave action propagation speed (in x and y direction) is given by:

The propagation speed in directional (\(\theta\)) space, where bottom refraction (first term) and current refraction (last two terms) are taken into account, is obtained from:

Dissipation

In XBeach there are three short wave dissipation processes that can be accounted for: wave breaking (\({D}_{w}\)), bottom friction (\({D}_{f}\)) and vegetation (\({D}_{v}\)). The three processes are explained in more detail in the following subsections.

Wave breaking

See also

Short wave dissipation by breaking is implemented in mod:roelvink_module.

Five different wave breaking formulations are implemented in XBeach. The formulations can be selected using the keyword break (Table 1).

Wave breaking formula |

Type of waves |

keyword |

|---|---|---|

Roelvink (1993a) |

Instationary |

roelvink1 |

Roelvink (1993a) extended |

Instationary |

roelvink2 |

Daly et al. (2010) |

Instationary |

roelvink_daly |

Baldock et al. (1998) |

Stationary |

baldock |

Janssen & Battjes (2007) |

Stationary |

janssen |

For the surf beat approach the total wave energy dissipation, i.e. directionally integrated, due to wave breaking can be modeled according to [Roelvink, 1993] (keyword: break = roelvink1). In the formulation of the dissipation due to wave breaking the idea is to calculate the dissipation with a fraction of breaking waves (\({Q}_{b}\)) multiplied by the dissipation per breaking event. In this formulation \(\alpha\) is applied as wave dissipation coefficient of O (keyword: alpha), \({T}_{rep}\) is the representative wave period and \({E}_{w}\) is the energy of the wave. The fraction of wave breaking is determined with the root-mean-square wave height (\({H}_{rms}\)) and the maximum wave height (\({H}_{max}\)). The maximum wave height is calculated as ratio of the water depth (\(h\)) plus a fraction of the wave height (\(\delta H_{rms}\), keyword: delta) using a breaker index \(\gamma\) (keyword: gamma). In the formulation for \({H}_{rms}\) the \(\rho\) represents the water density and \(g\) the gravitational constant. The total wave energy \({E}_{w}\) is calculated by integrating over the wave directional bins.

In variation of (11), one could also use another wave breaking formulation, presented in (12). This formulation is somewhat different than the formulation of [Roelvink, 1993] and selected using keyword break = roelvink2. The main difference with the original formulation is that wave dissipation with break = roelvink2 is proportional to \({H}^{3} / h\) instead of \({H}^{2}\).

Alternatively the formulation of [Daly et al., 2010] states that waves are fully breaking if the wave height exceeds a threshold (\(\gamma\)) and stop breaking if the wave height fall below another threshold (\(\gamma_{2}\)). This formulation is selected by break = roelvink_daly and the second threshold, \(\gamma_{2}\), can be set using keyword gamma2.

In case of stationary waves [Baldock et al., 1998] is applied (keyword: break = baldock), which is presented in (14). In this breaking formulation the fraction breaking waves \({Q}_{b}\) and breaking wave height \({H}_{b}\) are calculated differently compared to the breaking formulations used for the non-stationary situation. In \(\alpha\) is applied as wave dissipation coefficient, \({f}_{rep}\) represents a representative intrinsic frequency and \(y\) is a calibration factor.

Finally, it is possible to use the [Janssen and Battjes, 2007] formulation for wave breaking of stationary waves (keyword: break = janssen). This formulation is a revision of Baldock’s formulation.

In both the instationary or stationary case the total wave dissipation is distributed proportionally over the wave directions with the formulation in (16).

Bottom friction

See also

Short wave dissipation by bottom friction is implemented in func:wave_instationary_module/wave_instationary.

The short wave dissipation by bottom friction is modeled as

In (17) the \({f}_{w}\) is the short-wave friction coefficient. This value only affects the wave action equation and is unrelated to bed friction in the flow equation. Studies conducted on reefs (e.g. [Lowe et al., 2007]) indicate that \({f}_{w}\) should be an order of magnitude (or more) larger than the friction coefficient for flow (\({c}_{f}\)) due to the dependency of wave frictional dissipation rates on the frequency of the motion.

The derivation of the short wave dissipation term is based time-averaged instantaneous bottom dissipation using the Johnson friction factor \({f}_{w}\) of the bed shear stress:

The evaluation of the term \(\left\langle\left|\tilde{u}\right|^{3}\right\rangle\), the so-called third even velocity moment, depends on the situation. First we need expressions for the orbital velocity amplitude, which is expressed as:

In this formulation \({T}_{p}\) is the peak wave period, \({H}_{rms}\) is the root-mean-square wave height, \(k\) is the wave number and \(h\) is the local water depth.

If we consider the slowly-varying dissipation in wave groups, we need only to average over a single wave period and we can use a monochromatic (regular wave) expression. If we want to have the time-average dissipation over a full spectrum we get the best approximation from considering a linear Gaussian distribution. [Guza and Thornton, 1985] give pragmatic expressions for both cases.

For the monochromatic case:

For the linear Gaussian approximation:

Combining (18) and (20) we get:

In XBeach the orbital velocity amplitude is computed as in

orbital-velocity-monochromatic and the dissipation according to

(22), which is correct for the case

of instationary simulations on wave-group scale.

For the stationary case formulations (18) and (21) are similarly combined into:

Vegetation

See also

Short wave dissipation by vegetation is implemented in mod:vegetation_module.

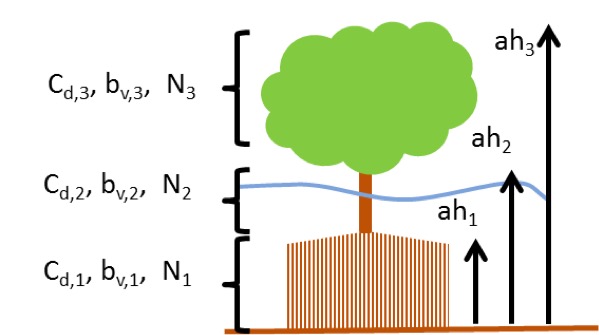

The presence of aquatic vegetation within the area of wave propagation or wave breaking results in an additional dissipation mechanism for short waves. This is modeled using the approach of [Mendez and Losada, 2004], which was adjusted by [Suzuki et al., 2012] to take into account vertically heterogeneous vegetation, see [van Rooijen et al., 2015]. The short wave dissipation due to vegetation is calculated as function of the local wave height and several vegetation parameters. The vegetation can be schematized in a number of vertical elements with each specific property. In this way the wave damping effect of vegetation such as mangrove trees, with a relatively dense root system but sparse stem area, can be modeled. The dissipation term is then computed as the sum of the dissipation per vegetation layer ([Suzuki et al., 2012]):

where \({D}_{v,i}\) is the dissipation by vegetation in vegetation layer \(i\) and \({n}_{v}\) is the number of vegetation layers. The dissipation per layer is given by:

where \(\widetilde{C}_{D,i}\) is a (bulk) drag coefficient, \({b}_{v,i}\) is the vegetation stem diameter, \({N}_{v,i}\) is the vegetation density, and \(\alpha_{i}\) is the relative vegetation height (= \({h}_{v} / h\)) for layer \(i\). In case only one vegetation layer is specified, the plants are assumed to be vertically uniform, which would for example typically apply in case of modeling sea grass.

Radiation stresses

Given the spatial distribution of the wave action (and therefore wave energy) the radiation stresses can be evaluated by using linear wave theory as described by:

Wave shape

See also

Wave shapes are implemented in func:morphevolution/RvR and func:morphevolution/vT.

The morphodynamic model considered is (short) wave averaged and resolves hydrodynamics associated with the wave group time scale. As a result the short wave shape is not solved for. However, as waves propagate from deep water onto beaches, their surface form and orbital water motion become increasingly non-linear because of the amplification of the higher harmonics.

There are two wave forms implemented to take this non-linearity into account:

A formulation of [Ruessink et al., 2012] based on a parameterization with the Ursell number. (keyword: waveform = ruessink_vanrijn)

A formulation of [van Thiel de Vries, 2009] based on the parameterized wave shape model of [Rienecker and Fenton, 1981] (keyword: waveform = vanthiel)

The formulation of [Ruessink et al., 2012] relies on parameterizations for the non-linearity parameter \(r\) and phase \(\Phi\). The parameterizations are based on a data set of 30.000+ field observations of the orbital skewness \({S}_{k}\) and asymmetry \({A}_{s}\), collected under non-breaking and breaking wave conditions. The only variable parameter is the Ursell number, since according to [Ruessink et al., 2012] the Ursell that includes \({H}_{s}\), \(T\) and \(h\), describes the variability in \({S}_{k}\) and \({A}_{s}\) well. The Ursell number is calculated with the equation below.

The value for the skewness and asymmetry is calculated with the use of a Boltzmann sigmoid. The skewness and asymmetry are a function of \(\Psi\). In the formulation of [Ruessink et al., 2012] the \({p}_{1:6}\) are used as parameterized factors on the data set of field observations.

Alternatively, [van Thiel de Vries, 2009] utilized and extended the wave shape model of [Rienecker and Fenton, 1981]. In this model the short wave shape is described by a Rienecker and Fenton lookup table with amongst others amplitudes non-linear components obtained with stream function theory. Therefore, wave skewness (\({S}_{k}\)) and asymmetry (\({A}_{s})\) is computed in each grid point based on the water depth, dimensionless wave height and dimensionless wave period.

For \(w\) equals one a skewed (Stokes) wave is obtained with high peaks and flat troughs whereas \(w\) equals zero results in an asymmetric (saw tooth) wave with steep wave fronts. It is hypothesized that the weighting \(w\) can be expressed as a function of wave skewness and asymmetry. The relation between the phase and the weighting is studied in more detail by [van Thiel de Vries, 2009] by varying \(w\) between zero and one in small steps and computing the amplitudes with Rienecker and Fenton for a range of wave heights, wave periods and water depths. It is found that a unique relation between \(w\) and \(\Phi\) exists for any combination of wave height, wave period and water depth that is described by:

As explained in the next section, short-wave turbulence can be computed averaged over the bore interval (\({T}_{bore}\)). The bore interval is directly related to the wave shape and hence requires the weighting function \(w\) is determined. For the formulation of [Ruessink et al., 2012] no exact wave shape is determined and therefore no bore interval can be calculated. Therefore this approach cannot be combined with bore averaged short-wave turbulence.

Turbulence

See also

Wave breaking induced turbulence is implemented in func:morphevolution/waveturb.

Wave breaking induced turbulence at the water surface has to be transported towards the bed in order to affect the up-stirring of sediment. [Roelvink and Stive, 1989] used an exponential decay model with the mixing length proportional to \({H}_{rms}\) to estimate the time averaged turbulence energy at the bed from turbulence at the water surface:

where \({k}_{b}\) is turbulence variance at the bed and \(k\) is the time averaged turbulence variance at the water surface.

There are three possibilities for the turbulence variance at the bed (\({k}_{b}\)) implemented into XBeach:

Wave averaged near-bed turbulence energy (keyword: turb = wave_averaged):

(31)\[k_{b} =\frac{\overline{k_{s} }}{\exp (h/L_{mix} )-1}\]Bore-averaged near-bed turbulence energy [#1]_ (keyword: turb = bore_averaged)

(32)\[k_{b} =\frac{\overline{k_{s} }\cdot T_{rep} /T_{bore} }{\exp (h/L_{mix} )-1}\]Not taking into account the turbulence variance at the bed (keyword: turb = none)

Both formulations make use of the wave-averaged turbulence energy (\({k}_{s}\)) and a mixing length (\({L}_{mix}\)). The wave averaged turbulence energy at the surface is computed from the roller energy dissipation and following [Battjes, 1975] in which \({D}_{r}\) is roller dissipation:

The mixing length (\({L}_{mix}\)) is expressed as thickness of the surface roller near the water surface and depends on the roller volume \({A}_{r}\) ([Svendsen, 1984]):

Roller energy balance

See also

The roller energy balance is implemented in func:wave_instationary_module/wave_instationary.

While the short wave action balance adequately describes the propagation and decay of organized wave energy, it has often been found that there is a delay between the point where the waves start to break (which is where you would expect the strongest radiation stress gradients to occur) and the point where the wave set-up and longshore current start to build. This transition zone effect is generally attributed to the temporary storage of shoreward momentum in the surface rollers. Several authors have analyzed the typical dimensions of such rollers and their effect on the radiation stress (e.g. [Longuet-Higgins and Turner, 1974], [Svendsen, 1984], [Roelvink and Stive, 1989], [Nairn et al., 1990], [Deigaard, 1993], [Stive and De Vriend, 1994]).

The rollers can be represented as a blob of water with cross-sectional area A that slides down the front slope of a breaking wave. The roller exerts a shear stress on the water beneath it equal to:

where \(\beta_{s}\) is the slope of the breaking wave front, \(R\) is the roller area and \(L\) is the wave length. The roller has a kinetic energy equal to:

and a contribution to the radiation stress equal to:

We can now formulate an energy balance for the roller as follows:

where \(S\) is the loss of organized wave motion due to breaking and \(D\) is the dissipation. The latter is equal to the work done by the shear stress between the roller and the wave:

Given the complex motion in the breaking waves, we can only give approximate estimates of the order of magnitude of the parameters in equations (35) till (39). Various authors have suggested that the velocity in the roller can be approximated as purely horizontal and equal to the wave celerity \({c}_{g}\). In that case we get (for waves travelling in x-direction):

However, this must be seen as an (unrealistic) upper limit on the radiation stress contribution as this can only be valid for \({w}_{roller}=0\). [Nairn et al., 1990] showed that the conceptual model of [Roelvink and Stive, 1989] would lead to a factor 0.22 instead of 2. However, a ratio in the order of 1 seems more realistic. [Stive and De Vriend, 1994] found a discrepancy between the roller shear stress derived from an energy balance and that derived from the momentum balance, in the order of a factor two. They explained this by a complicated analysis of the effect of water entering and leaving the roller, which led to a modification of the propagation term in the roller energy balance by a factor two. As this leads to the unphysical result that rollers would propagate at twice the wave celerity, we believe that the discrepancy must be sought in the ratio between roller energy and radiation stress contribution. Therefore we stick to the roller energy balance suggested by [Nairn et al., 1990] in equation (41) and the roller contribution to the radiation stress:

This leads to an elegant and consistent distribution of the wave-induced forcing through the surfzone. To close the roller energy balance we need to express the dissipation of the roller as a function of \({E}_{r}\). This can be done by introducing:

Combining this with equations (36) and (42) we then find:

The coefficients \(\beta_{s}\) and \(\beta_{u}\) are usually lumped together into a single coefficient. This coefficient \(\beta\) is in the O (keyword: beta), which may vary through the surf zone. The forcing of the longshore current by the radiation stress gradient can be derived from the wave and roller energy balances and :

In a longshore uniform situation, according to Snell’s law, the first term on the right-hand side equals zero; the second term exactly equals the sum of the wave energy dissipation and the roller energy input and dissipation terms, so the forcing term reduces to:

Shallow water equations

See also

The shallow water equations are implemented in func:flow_timestep_module/flow.

For the low-frequency waves and mean flows we use the shallow water equations. To account for the wave induced mass-flux and the subsequent (return) flow these are cast into a depth-averaged Generalized Lagrangian Mean (GLM) formulation ([Andrews and Mcintyre, 1978], [Walstra et al., 2000]). In such a framework, the momentum and continuity equations are formulated in terms of the Lagrangian velocity \({u}^{L}\) which is defined as the distance a water particle travels in one wave period, divided by that period. This velocity is related to the Eulerian velocity (the short-wave-averaged velocity observed at a fixed point) by:

where \({u}^{S}\) and \({v}^{S}\) represent the Stokes drift in x- and y-direction respectively ([Phillips, 1977]). The Strokes drift is calculated with in which the wave-group varying short wave energy \({E}_{w}\) and direction are obtained from the wave-action balance.

The resulting GLM-momentum equations are given by:

where \(\tau_{sx}\) and \(\tau_{sy}\) are the wind shear stresses, \(\tau_{bx}\) and \(\tau_{by}\) are the bed shear stresses, \(\eta\) is the water level, \({F}_{x}\) and \({F}_{y}\) are the wave-induced stresses, \({F}_{v,x}\), and \({F}_{v,y}\) are the stresses induced by vegetation, \(\nu_{h}\) is the horizontal viscosity and \(f\) is the Coriolis coefficient. Note that the shear stress terms are calculated with the Eulerian velocities as experienced by the bed and not with the GLM velocities, as can be seen in .

Horizontal viscosity

See also

The Smagorinsky model is implemented in func:flow_timestep_module/visc_smagorinsky.

The horizontal viscosity (\({v}_{h}\)) is by default computed using the [Smagorinsky, 1963] model to account for the exchange of horizontal momentum at spatial scales smaller than the computational grid size, which is given as:

In \({c}_{S}\) is the Smagorinsky constant (keyword: nuh), set at 0.1 in all model simulations. It is also possible to use a user-defined value for the horizontal viscosity by turning off the Smagorinsky model (keyword: smag = 0) and specifying the value directly (also keyword: nuh).

Bed shear stress

See also

Bed shear stresses are implemented in mod:bedroughness_module.

The bed friction associated with mean currents and long waves is included via the formulation of the bed shear stress (\(\tau_{b}\)). Using the approach of [Ruessink et al., 2001] the bed shear stress is calculated with:

There are 5 different formulations in order to determine the dimensionless bed friction coefficient \({c}_{f}\) (keyword: bedfriction) implemented in XBeach (Table 2).

Bed friction formulation |

Relevant coefficient |

keyword |

|---|---|---|

Dimensionless friction coefficient |

\({c}_{f}\) |

cf |

Chezy |

C |

chezy |

Manning |

n |

manning |

White-Colebrook |

\({k}_{s}\) |

white-colebrook |

White-Colebrook grain size |

D90 |

white-colebrook-grainsize |

The dimensionless friction coefficient can be calculated from the Chezy value with equation (51). A typical Chezy value is in the order of \(55 {m}^{1/2}/s\).

In the Manning formulation the Manning coefficient (\(n\)) must be specified. The dimensionless friction coefficient is calculated from equation (52). Manning can be seen as a depth-dependent Chezy value and a typical Manning value would be in the order of \(0.02 s/{m}^{1/3}\).

In the White-Colebrook formulation the geometrical roughness of Nikuradse (\({k}_{s}\)) must be specified. The dimensionless friction coefficient is calculated from equation (53) The White-Colebrook formulation has al log relation with the water depth and a typical \({k}_{s}\) value would be in the order of 0.01 - 0.15 m.

The option of White-Colebrook based on the grain size is somewhat different than the other four formulations. This formulation is based on the relation between the \({D}_{90}\) of the top bed layer and the geometrical roughness of Nikuradse according to equation (54). The user does not have to specify a value for the bed friction coefficient.

Values of the drag coefficient for different seabed sediment grain sizes (flat beds) and similarly for bed form scenarios have been empirically derived from field and laboratory data in previous studies for different bed friction coefficients. The value of the friction coefficient (\(C\), \({c}_{f}\), \(n\) or \({k}_{s}\)) can be defined with one single value (keyword: bedfriccoef) or for a separate value per grid cell (keyword: bedfricfile).

In XBeach-G, the bed shear stress is described in terms of a drag and an inertia component. This approach allows the effect of acceleration on sediment transport to be explicitly taken into account in the bed shear stress, rather than in a modification of the effective Shields parameter.

where \(\tau_{bd}\) and \(\tau_{bi}\) are bed shear stress terms due to drag and inertia, respectively. Note that the inertia component of the bed shear stress does not represent the actual inertia of the particles, but refers to the force on particles in the bed due to pressure gradients, as well as due to the disturbance of the accelerating flow, following potential flow theory.

The bed shear stress due to drag is computed with the XBeach-G default of White-Colebrook grain size (keyword: bedfriction=white-colebrook-grainsize). The bed friction factor \(c_{f}\) is computed following the description of [Conley, 1994] to account for modified bed shear stress due to ventilated boundary layer effects in areas of infiltration and exfiltration

Bed shear due to inertia effects (keyword: friction_acceleration) is computed through analogy with the force exerted by water on a sphere in non-stationary flow. In this case, the force on an object due to inertia \(F_{i}\) can be computed from the local flow acceleration:

where \(c_{m}=1+c_{a}\) is an inertia coefficient, \(c_{a}\) is the added mass coefficient \(c_{a}=0.5\) for spheres with zero autonomous acceleration),:math:c_{v} is the volume shape factor (\(c_{v}=\frac{\pi}{6}\) for spheres) and \(D\) is the characteristic grain size. Note that the inertial force is therefore the sum of the Froude Krylov force \(\rho c_{v}D^{3}\frac{\partial u}{\partial t}\) and the hydrodynamic mass force \(\rho c_{a}c_{v}D^{3}\frac{\partial u}{\partial t}\). For the purpose of XBeach-G, the shear stress on the bed due to inertia is computed by assuming the characteristic grain size to be the median sediment grain size and the number of grains affected by flow acceleration per unit area to scale with \(c_{n} D_{50}\) such that:

XBeach-G supports two different formulation to compute the bed shear due to inertia effects (keyword: friction_acceleration): the McCall equation and the Nielsen equation. In the case of the McCall equation (keyword: friction_acceleration = McCall), ROBERT. In the case of the Nielsen equation (keyword: friction_acceleration = Nielsen), ROBERT.

Damping by vegetation

See also

Infra-gravity wave damping by vegetation is implemented in mod:vegetation_module.

The presence of aquatic vegetation within the area of wave propagation or wave breaking may not only result in short wave dissipation (Dissipation), but also in damping of infragravity waves and/or mean flow. Since both long waves and mean flow are fully resolved with the nonlinear shallow water equations, the effect of vegetation can be modeled using a drag force (e.g. [Dalrymple et al., 1984]), which can be directly added to the momentum equations ([van Rooijen et al., 2015], equation (48)):

Where \({C}_{D}\) is a drag coefficient, \({b}_{v}\) is the vegetation stem diameter, \(N\) is the vegetation density and \(u\) is the wave or current related velocity. To take into account the velocity due to mean flow and infragravity waves, we use the Lagrangian velocity (\({u}^{L}\)) here. The vegetation-induced time varying drag force is then calculated as the sum of the vegetation-induced drag force per vegetation layer:

where \(\widetilde{C}_{D,i}\) is a (bulk) drag coefficient, \({b}_{v,i}\) is the vegetation stem diameter, \({n}_{v,i}\) is the vegetation density, and \({h}_{v,i}\) is the vegetation height for layer \(i\).

Porous in-canopy flow

To include the resistance of corals in the simulations or when the in-canopy velocity is required, the porous in-canopy model can be applied. This model computes the flow though the coral canopy, based on the porosity (\(\epsilon\)) and canopy height (\(h_c\)). The in-canopy cell is formulated within the flow grid-cell, which means that the forcing of the flow is used as forcing terms in the canopy cell. The horizontal in-canopy momentum equation, derived by [Lowe et al., 2008], is given as,

Where \(\lambda_p\) is the dimensional plan area (\(1-\epsilon\)), \(h_c\) the canopy height, \(\mu\) the kinematic viscosity, \(K_p\) the laminar permeability, \(\beta\) a drag coefficient and \(C_f\) an empirical friction factor. Based on the in-canopy flow, the canopy-induced force (on the mean flow) can be derived. This canopy-induced force is given as,

This canopy-induced force is included in the horizontal momentum equation (48) to represent the resitsance of the corals. For emergent corals, the canopy height is bounded by the water depth.

Wind

The first term on the right hand side of the momentum equations (equation (48)) represents the forcing due to the wind stress. These forcing terms due to the wind are formulated as:

where \(\tau_{w}\) is wind stress, \(\rho_{a}\) is density of air, \({C}_{d}\) is the wind drag the coefficient, \(W\) is the wind velocity. The wind stress is turned off by default, and can be turned on specifying a constant wind velocity (keyword: windv) or by specifying a time varying wind file.

Rainfall (beta feature)

It is possible to include rainfall in the simulation. Based on a constant or temporally- and/or spatially-varying rainfall rate (\(q_{rain}\)), the continuity equation is given by,

Note that this functionality is a beta feature and not fully tested.

Non-hydrostatic pressure correction

See also

The non-hydrostatic pressure correction is implemented in mod:nonh_module.

For non-hydrostatic XBeach calculations (keyword: waveform = nonh) depth-averaged flow due to waves and currents are computed using the non-linear shallow water equations, including a non-hydrostatic pressure. The non-hydrostatic model accounts for all wave motions (including short waves) within the shallow water equations, so the wave action balance should be turned off (keyword: swave = 0). The depth-averaged normalized dynamic pressure (\(q\)) is derived in a method similar to a one-layer version of the SWASH model ([Zijlema et al., 2011]). The depth averaged dynamic pressure is computed from the mean of the dynamic pressure at the surface and at the bed by assuming the dynamic pressure at the surface to be zero and a linear change over depth. In order to compute the normalized dynamic pressure at the bed, the contributions of advective and diffusive terms to the vertical momentum balance are assumed to be negligible.

In \(w\) is the vertical velocity and \(z\) is the vertical coordinate. The vertical velocity at the bed is set by the kinematic boundary condition:

Combining the Keller-box method ([Lam and Simpson, 1976]), as applied by [Stelling and Zijlema, 2003] for the description of the pressure gradient in the vertical, the dynamic pressure at the bed can be described by:

Substituting in allows the vertical momentum balance at the surface to be described by:

In the subscript \(s\) refers to the location at the surface. The dynamic pressure at the bed is subsequently solved by combining and the local continuity equation:

In order to improve the computed location and magnitude of wave breaking, the hydrostatic front approximation (HFA) of [Smit et al., 2014] is applied, in which the pressure distribution under breaking bores is assumed to be hydrostatic. Following the recommendations of [Smit et al., 2014], we consider hydrostatic bores if \(\frac{\delta \eta }{\delta t} >0.6\) and reform if \(\frac{\delta \eta }{\delta t} <0.3\). The values can respectively be changed with the keywords maxbrsteep and secbrsteep.

Although this method greatly oversimplifies the complex hydrodynamics of plunging waves, [McCall et al., 2014] shows that the application of this method provides sufficient skill to describe dominant characteristics of the flow, without requiring computationally expensive high-resolution discretization of the vertical and surface tracking of overturning waves.

Reduced two layer model (nh+)

See also

The non-hydrostatic pressure correction is implemented in mod:nonh_module.

The reduced two layer model was implemented to improve the dispersive behaviour of the non-hydrostatic model (keyword: par:nhq3d). Due to the additional layer, frequency dispersion is more accurately modelled than with the depth-averaged formulation. Mostly, the addition of an extra layer will increase the computational time significantly, but a simplified (reduced) lower layer is applied to reduce the extra computational effort. It is assumed that the non-hydrostatic pressure is constant in the lower layer. This means that the non-hydrostatic pressure at the bottom has the same value as the non-hydrostatic pressure between the layers. Still the non-hydrostatic pressure at the surface is zero, which means that for every location in the domain there is one non-hydrostatic unknown.

To make the simplification of the reduced layer, the layer velocities are transformed to a depth-averaged velocity \(U\) and a velocity difference \(\Delta u\) according to,

Where \(\alpha\) is the layer distribution. Then, the momentum equations for \(U\), \(\Delta u\) and \(w_2\) are given by,

Due to the simplified non-hydrostatic pressure in the lower layer, the vertical velocity between the layers is neglected. Thus, only the continuity relation for the upper layer is required. This relation in terms of the reduced two layer formulation is given as,

To determine the water elevation, the global continuity equation is applied,

These equatuons are used to solve \(U\), \(\Delta u\), \(w_2\) and \(\xi\)

When using the reduced two layer model, the model is forced with both \(U\) and \(\Delta u\). Linear wave theory is used to generate the layer-averaged velocities, which can be transformed to \(U\) and \(\Delta u\) by applying equation (70).

Groundwater flow

See also

Groundwater flow is implemented in mod:groundwaterflow.

The groundwater module (keyword: gwflow = 1) in XBeach utilizes the principle of Darcy flow for laminar flow conditions and a parameterization of the Forchheimer equations for turbulent groundwater flow. The module includes a vertical interaction flow between the surface water and groundwater. This flow is assumed to be a magnitude smaller than the horizontal flow and is not incorporated in the momentum balance.

Continuity

In order to solve mass continuity in the groundwater model, the groundwater is assumed to be incompressible. Continuity is achieved by imposing a non-divergent flow field:

where \(U\) is the total specific discharge velocity vector, with components in the horizontal (\({u}_{gw}\), \({v}_{gw}\)) and vertical (\({w}_{gw}\)) direction:

Equation of motions

Laminar flow of an incompressible fluid through a homogeneous medium can be described using the well-known Law of [Darcy, 1856], valid for laminar flow conditions (keyword: gwscheme = laminar)

in which \(K\) is the hydraulic conductivity of the medium (keyword: \(kx\) \(ky\), \(kz\), for each horizontal and vertical direction) and \(H\) is the hydraulic head.

In situations in which flow is not laminar, turbulent and inertial terms may become important. In these cases the user can specify XBeach to use a method (keyword: gwscheme = turbulent) that is comparable with the USGS MODFLOW-2005 groundwater model ([Harbaugh, 2005]), in which the turbulent hydraulic conductivity is estimated based on the laminar hydraulic conductivity (\({K}_{lam}\)) and the Reynolds number at the start of turbulence (\({Re}_{crit}\)) ([Halford, 2000]):

In the Reynolds number (\(Re\)) is calculated using the median grain size (\({D}_{50}\)), the kinematic viscosity of water (\(\nu\)) and the groundwater velocity in the pores (\(U/n_{p}\)), where \({n}_{p}\) is the porosity. Similar expressions exist for the other two components of the groundwater flow.

The critical Reynolds number for the start of turbulence (\({Re}_{crit}\)) is specified by the user, based on in-situ or laboratory measurements, or expert judgment (keyword: gwReturb). Since the hydraulic conductivity in the turbulent regime is dependent on the local velocity, an iterative approach is taken to find the correct hydraulic conductivity and velocity.

Determination of the groundwater head

The XBeach groundwater model allows two methods to determine the groundwater head: a hydrostatic approach (keyword: gwnonh = 0) and a non-hydrostatic approach (keyword: gwnonh = 1).

Hydrostatic approach

In the hydrostatic approach, the groundwater head is computed as follows:

In cells where there is no surface water the groundwater head is set equal to the groundwater surface level \(\eta_{gw}\).

In cells where there is surface water, but the groundwater surface level \(\eta_{gw}\) is more than \({d}_{wetlayer}\) (keyword: dwetlayer) below the surface of the bed, the groundwater head is set equal to the groundwater surface level.

In cells where there is surface water and the groundwater surface level \(\eta_{gw}\) is equal to the surface of the bed, the groundwater head is set equal to the surface water level.

In cells where there is surface water and the groundwater surface level \(\eta_{gw}\) is equal to or less than \({d}_{wetlayer}\) below the surface of the bed, the groundwater head is linearly weighted between that of the surface water level and the groundwater level, according to the distance from the groundwater surface to the surface of the bed.

It should be noted that the numerical parameter \({d}_{wetlayer}\) is required to ensure numerical stability of the hydrostatic groundwater model. Larger values of \({d}_{wetlayer}\) will increase numerical stability, at the expense of numerical accuracy.

Non-hydrostatic approach

Groundwater flow in the swash and surf zone has been shown to be non-hydrostatic (e.g., [Li and Barry, 2000]; [Lee et al., 2007]). In order to capture this, it may be necessary in certain cases to reject the Dupuit–Forchheimer assumption of hydrostatic groundwater pressure.

In the non-hydrostatic approach, the groundwater head is not assumed to be constant in the vertical. Since XBeach is depth-averaged, the model cannot compute true vertical profiles of the groundwater head and velocity. In order to estimate of the groundwater head variation over the vertical, a quasi-3D modeling approach is applied, which is set by two boundary conditions and one non-hydrostatic shape assumption:

There is no exchange of groundwater between the aquifer and the impermeable layer below the aquifer.

The groundwater head at the upper surface of the groundwater is continuous with the head applied at the groundwater surface.

The shape of the non-hydrostatic head profile is parabolic (keyword: gwheadmodel = parabolic), implying that the vertical velocity increases or decreases linearly from the bottom of the aquifer to the upper surface of the groundwater, or the non-hydrostatic head profile is hyperbolic (keyword: gwheadmodel = exponential), cf., [Raubenheimer et al., 1999].

The vertical groundwater head approximation can be solved for the three imposed conditions by a vertical head function, shown here for the parabolic head assumption. The depth-average value of the groundwater head is used to calculate the horizontal groundwater flux and is found by integrating the groundwater head approximation over the vertical:

In the mean vertical ground water head (\(H\)) is calculated using the groundwater head imposed at the groundwater surface (\({H}_{bc}\)), the groundwater head parabolic curvature coefficient (\(\beta\)) and the height of the groundwater level above the bottom of the aquifer (\({h}_{gw}\)).

The unknown curvature coefficient (\(\beta\)) in the vertical groundwater head approximation is solved using the coupled equations for continuity and motion (equations (76) and (78)), thereby producing the depth-average horizontal groundwater head gradients and vertical head gradients at the groundwater surface.

Although the requirement for non-hydrostatic pressure has the benefit of being a more accurate representation of reality, and does not require the numerical smoothing parameter \({d}_{wetlayer}\), resolving the non-hydrostatic pressure field can be computationally expensive, particularly in 2DH applications.

Exchange with surface water

In the groundwater model there are three mechanisms for the vertical exchange of groundwater and surface water: 1) submarine exchange, 2) infiltration and 3) exfiltration. The rate of exchange between the groundwater and surface water (\(S\)) is given in terms of surface water volume, and is defined positive when water is exchanged from the surface water to the groundwater.

Infiltration and exfiltration can only occur in locations where the groundwater and surface water are not connected. Infiltration takes place when surface water covers an area in which the groundwater level is lower than the bed level. The flux of surface water into the bed is related to the pressure gradient across the wetting front.

In equation (81) the surface water-groundwater exchange flow of infiltration (\({S}_{inf}\)) is calculated using the effective hydraulic conductivity (\(K\)), the surface water pressure at the bed (\(\left. p\right|^{z=\xi }\)) and the thickness of the wetting front (\(\delta_{infill}\)).

Since the groundwater model is depth-averaged and cannot track multiple layers of groundwater infiltrating into the bed, the wetting front thickness is reset to zero when there is no available surface water, the groundwater exceeds the surface of the bed, or the groundwater and the surface water become connected. In addition, all infiltrating surface water is instantaneously added to the groundwater volume, independent of the distance from the bed to the groundwater table. Since the groundwater model neglects the time lag between infiltration at the beach surface and connection with the groundwater table a phase error may occur in the groundwater response to swash dynamics

Exfiltration (\({S}_{exf}\)) occurs where the groundwater and surface water are not connected and the groundwater level exceeds the bed level. The rate of exfiltration is related to the rate of the groundwater level exceeding the bed level.

Submarine exchange (\({S}_{sub}\)) represents the high and low frequency infiltration and exfiltration through the bed due pressure gradients across the saturated bed. This process only takes place where the groundwater and surface water are connected. In the case of the non-hydrostatic groundwater model, the rate of submarine exchange is determined by the vertical specific discharge velocity at the interface between the groundwater and surface water. The value of this velocity can be found using the vertical derivative of the approximated groundwater head at the groundwater-surface water interface (shown for the parabolic head approximation).

In the case of the hydrostatic groundwater model, the difference between the surface water head and the groundwater head is used to drive submarine discharge when the groundwater level is less than \({d}_{wetlayer}\) from the bed surface.

While most beach systems can acceptably described through vertical exchange of surface water and groundwater, in cases of very steep permeable slopes (e.g., porous breakwaters), it is necessary to include the horizontal exchange of groundwater and surface water between neighboring cells (keyword: gwhorinfil = 1). In this case the horizontal head gradient between the surface water and groundwater across vertical interface between the cells is used to determine the horizontal exchange flux:

where \(\delta H_{s}\) is the head gradient between the surface water and groundwater in neighboring cell, \(\delta s\) is the gradient distance, defined as the numerical grid size, and \(A\) is the surface area through which the exchange takes place, defined as the difference in bed level between the neighboring cells.

Calculation of groundwater and surface water levels

Groundwater levels are updated through the continuity relation:

In these same areas the surface water level is modified to account for exchange fluxes:

Boundary conditions

Since the groundwater dynamics are described by a parabolic equation, the system of equations requires boundary conditions at all horizontal and vertical boundaries, as well as an initial condition:

Sediment transport

See also

Sediment transport is implemented in func:morphevolution/transus.

Advection-diffusion equation

Sediment concentrations in the water column are modeled using a depth-averaged advection-diffusion scheme with a source-sink term based on equilibrium sediment concentrations ([Galappatti and Vreugdenhill, 1983]):

In \(C\) represents the depth-averaged sediment concentration which varies on the wave-group time scale and \({D}_{h}\) is the sediment diffusion coefficient. The entrainment of the sediment is represented by an adaptation time \({T}_{s}\), given by a simple approximation based on the local water depth \(h\) and sediment fall velocity \({w}_{s}\). A small value of \({T}_{s}\) corresponds to nearly instantaneous sediment response. The adaptation time is limited with a minimum period (\({T}_{s,min}\)) which is defined as a factor (dtlimts) times the timestep. The factor \({f}_{Ts}\) is a correction and calibration factor to take into account the fact that \({w}_{s}\) is determined on depth-averaged data (keyword: tsfac).

The entrainment or deposition of sediment is determined by the mismatch between the actual sediment concentration \(C\) and the equilibrium concentration \({C}_{eq}\) thus representing the source term in the sediment transport equation.

The sediment transport rate, required for the bed level update, is defined as (shown for the x-direction),

General parameters

In the sediment transport formulations, the equilibrium sediment concentration \({C}_{eq}\) (for both the bed load and the suspended load) is related to the velocity magnitude (\({v}_{mg}\)), the orbital velocity (\({u}_{rms}\)) and the fall velocity (\({w}_{s}\)). This section elaborates how these are calculated. Important to note: XBeach calculates the equilibrium concentration for the bed and suspended load separately.

First of all the Eulerian , if long wave stirring is turned on (keyword: lws = 1), the velocity magnitude \({v}_{mg}\) is equal to the magnitude of the Eulerian velocity, as can be seen in .

If wave stirring is turned off (keyword: lws = 0), the velocity magnitude will be determined by two terms: first of all a factor of the velocity magnitude of the previous time step (\({v}_{mg}^{n-1}\)) and secondly a current-averaged part. Averaging will be carried out based on a certain factor \({f}_{cats}\) (keyword: cats) of the representative wave period \({T}_{rep}\).

Secondly, the , the \({u}_{rms}\) is obtained from the wave group varying wave energy using linear wave theory. In this formulation \({T}_{rep}\) is the representative wave period and the \({H}_{rms}\) is the root-mean-square wave height. In this equation the water depth is enhanced with a certain factor of the wave height (keyword: delta).

To account for wave breaking induced turbulence due to short waves, the orbital velocity is adjusted ([van Thiel de Vries, 2009]). In this formulation \({k}_{b}\) is the wave breaking induced turbulence due to short waves. The turbulence is approximated with an empirical formulation in XBeach.

Thirdly, the , the \({w}_{s}\) is calculated using the formulations of [Ahrens, 2000] which are derived based on a relationship suggested by [Hallermeier, 1981]:

For high sediment concentrations, the fall velocity is reduced (keyword: fallvelred = 1) using the expression of [Richardson and Zaki, 1954]:

The exponent a is estimated using the equation of [Rowe, 1987], which depends purely on the Reynolds particle number R:

Transport formulations

See also

The sediment transport formulations are implemented in func:sedtransform

In the present version of XBeach, two sediment transport formulations are available. The formulae of the two formulations are presented in the following sections. For both methods the total equilibrium sediment concentration is calculated with equation (99). In this equation the minimum value of the equilibrium sediment concentration (for both bed load en suspended load) compared to the maximum allowed sediment concentration (keyword: cmax).

The transport formulations implemented into XBeach distinguishes bed load and suspended load transport. It is possible to in- and exclude these transports components (keywords: bed & sus, with bed = 1 will include bed load transport). There is also a possibility to compute the total bulk transport rather than bed and suspended load separately (keyword: bulk = 1). The bed load will be calculated if it is suspended transport. On top of that this switch will have impact on how the bed slope effect (see Section 2.7.6) will be calculated

Soulsby-Van Rijn

The first possible sediment transport formulation are the Soulsby-Van Rijn equations (keyword: form = soulsby_vanrijn) ([Soulsby, 1997]; [van Rijn, 1985]). The equilibrium sediment concentrations are calculated according to:

For which the bed load and suspended load coefficients are calculated with:

In which the dimensionless sediment diameter (D*) can be calculated with the following formulation. The \(v\) is the kinematic viscosity based on the expression of Van Rijn and is a function of the water temperature. XBeach assumes a constant temperature of 20 degrees Celsius, this result in a constant kinematic viscosity of \({19}^{-6} {\rm m}^{2}/{\rm s}\).

The critical velocity (\({U}_{cr}\)) defines at which depth averaged velocity sediment motion is initiated:

Finally the drag coefficient (\({C}_{d}\)) is calculated with equation (104). A drag coefficient is used to determine the equilibrium sediment concentrations. On top of that [Soulsby, 1997] gives a relation between the bed shear stress of the depth-averaged current speed.

In this equation \(z_0\) is used for the bed roughness length and is used as zero flow velocity level in the formulation of the sediment concentration. In XBeach this is a fixed value (keyword: z0), but [Soulsby, 1997] argues there is a relation between the Nikuradse and kinematic viscosity.

Van Thiel-Van Rijn

The second possible sediment transport formulation are the Van Thiel-Van Rijn transport equations (keyword: form = vanthiel_vanrijn) ([van Rijn, 2007]; [van Thiel de Vries, 2009]). The major difference between the Soulsby - Van Rijn equations is twofold. First of all, there is no drag coefficient calculated anymore and secondly the critical velocity is determined by calculating separately the critical velocity for currents (\({U}_{crc}\)) according to [Shields, 1936] and for waves (\({U}_{crw}\)) according to [Komar and Miller, 1975].

The equilibrium sediment concentrations are calculated according to

For which the bed-load and suspended load coefficient are calculated with:

The critical velocity is computed as weighted summation of the separate contributions by currents and waves ([van Rijn, 2007]):

The critical velocity for currents is based on [Shields, 1936]:

The critical velocity for waves is based on [Komar and Miller, 1975]:

Van Rijn (1993)

The third possible sediment transport formulation are the Van Rijn (1993 equations (keyword: form = vanrijn1993) Van Rijn (1993) distinguishes between sediment transport below the reference height at which sediment is treated as bed-load transport and above the reference height which is treated as suspended-load.

The bed-load transport is computed with

In which the sediment mobility number due to waves and currents ( (\({M}\)) ) can be calculated with the following formulation with (\({v}_{e}\)) being the effective velocity. The excess sediment mobility number ( (\({M}_{e}\)) ) is computed with the difference between the effective and critical velocity ( (\({v}_{cr}\)) ).

For the suspended-load, first the reference concentration is calculated in accordance with ([Van Rijn, 1984])

Secondly, the concentration profile is resolved by calculating the bed-shear stresses due to waves and currents and estimating the concentration profile where the combined bed shear stress exceeds the critical bed shear stress. Depth-averaged mixing due to waves and currents.

Implementation of increased sediment grain size dependency

The default sediment transport relations in XBeach are not greatly sensitive to the sediment grain size (equilibrium sediment concentration approximately proportional to \({D}_{50}^{-0.8}\) and bed load transport approximately proportional to \({D}_{50}^{0.45}\). Addition processes such as infragravity waves and wave turbulence often further decrease the sensitivity of the model morphodynamics to the grain size.

To increase model sensitivity to grain size, a calibration term on the equilibrium sediment concentration and nonlinear wave-driven transport has been developed based on the work of [Steetzel, 1993].

The increased grain size sensitivity in this approach is achieved firstly by updating the equilibrium concentration at each time step, such that this concentration becomes relatively larger for small grain sizes, and smaller of large grain sizes:

In which \({C}_{eq,update}\) is the updated equilibrium concentration, \({D}_{50,ref}=225 \mu m\) is a fixed reference grain size, and \(\alpha_{D50} \geq 0\) is a calibration factor for the sensitivity set by keyword alfaD50.

The sensitivity to grain size is secondly increased through a modification of the effective sediment transport velocity in the direction of the waves due to nonlinear wave effects (\(u_{a}\) , see Section Effects of wave non-linearity ):

In which \({u}_{a,update}\) is the updated effective transport velocity. In this approach, the effective transport velocity in the direction of the waves increases (i.e., greater onshore transport) for grainsizes greater than \({D}_{50,ref}\), and decreases for grain sizes smaller than \({D}_{50,ref}\). By default, alfaD50 is set to 0, which means that the sediment transport rate is computed without increased grain size sensitivity.

Gravel formulations

In XBeach-G, gravel sediment transport is, by default, computed using the bed load transport equation of [van Rijn, 2007], excluding coefficients for silt:

where \(q_{b}\) is the volumetric bed load transport rate (excluding pore space), \(gamma\) is a calibration coefficient, set to 0.5 in [van Rijn, 2007], \(D_{*}=D_{50}\left(\frac{\Delta g}{\nu^{2}}\right)^{\frac{1}{3}}\) is the non-dimensional grain size, and \(theta_{cr}\) is the critical Shields parameter for the initiation of transport, in this thesis computed using the relation of [Soulsby, 1997].

In the case of the Nielsen equation is applied, the sediment transport model is modified slightly from that presented in Chapter ref{chap:Morphodynamics}. In this model the total gravel sediment transport is computed using a modification of the citet{Meyer-Peter1948} equation for bed load transport derived by citet{Nielsen2002}:

Besides the McCall - Van Rijn and the Nielsen equation there are several other sediment gravel transport formulae implemented in XBeach-G. For more information on XBeach-G, download the PhD thesis of McCall (2015) on URL: URL: [http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/3929]_.

Sediment transport formulae |

keyword |

|---|---|

McCall - Van Rijn |

mccall_vanrijn |

Nielsen (2006) |

nielsen2006 |

Wilcock & Crow |

wilcock_crow |

Engelund & Fredsoe |

engelund_fredsoe |

Meyer-Peter & Muller |

mpm |

Wong & Parker |

wong_parker |

Fernandez Luque & van Beek |

fl_vb |

Fredoe & Deigaard |

fredsoe_deigaard |

Effects of wave non-linearity

Effects of wave skewness and asymmetry are accounted for in the advection-diffusion equation, repeated here:

XBeach considers the wave energy of short waves as averaged over their length, and hence does not simulate the wave shape. A discretization of the wave skewness and asymmetry was introduced by [van Thiel de Vries, 2009], to affect the sediment advection velocity. In this equation \({u}_{a}\) is calculated as function of wave skewness (\({S}_{k}\)), wave asymmetry parameter (\({A}_{s}\)), root-mean square velocity \({u}_{rms}\) and two calibration factor \({f}_{Sk}\) and \({f}_{As}\) (keyword: facSk & facAs), see equation (119). To set both values one can use the keyword: facua. The method to determine the skewness and asymmetry is described in section 2.3.4. A higher value for \({u}_{a}\) will simulate a stronger onshore sediment transport component.

Hindered erosion by dilatancy

Under overwash and breaching conditions (high flow velocities and large bed level variations in time), dilatancy might hinder the erosion rates ([de Vet, 2014]). To account for this effect, the theory of [van Rhee, 2010] could be applied (keyword: dilatancy = 1), reducing the critical Shields parameter at high flow velocities:

In this equation, \({v}_{e}\) refers to the erosion velocity, \({k}_{l}\) is the permeability, \(n0\) is the porosity prior, \({n}_{l}\) is the porosity in the sheared zone (keyword: pormax) and the parameter \(A\) (keyword: rheeA) is equal to 3/4 for single particles and approximately 1.7 for a continuum.

The larger the permeability of the bed, the smaller the dilatancy effect. [van Rhee, 2010] suggests using the equation proposed by [den Adel, 1987]:

Finally, the erosion velocity \({v}_{e}\), is the velocity at which the bottom level decreases:

Bed slope effect

The bed slope affects the sediment transport in various ways ([Walstra et al., 2007]):

The bed slope influences the local near-bed flow velocity;

The bed slope may change the transport rate once the sediment is in motion;

The bed slope may change the transport direction once the sediment is in motion;

The bed slope will change the threshold conditions for initiation of motion.

The influence of the bed slope on the local hydrodynamics is not considered in XBeach.

Two possible expressions are implemented to change the magnitude of the sediment transport. The first method is the default one in XBeach:

This method could be applied on either the total sediment transport (keyword: bdslpeffmag = roelvink_total) or only on the bed load transport (keyword: bdslpeffmag = roelvink_bed). The second method is based on the engineering formula of [Soulsby, 1997]:

Also this method could be applied on the total transport (keyword: bdslpeffmag = soulsby_total) or on the bed load transport only (keyword: bdslpeffmag = soulsby_total). To change the direction of the bed load transport, the expressions of [van Bendegom, 1947] and [Talmon et al., 1995] could be used (keyword: bdslpeffdir = talmon):

Finally, it is possible to adjust the initiation of motion criteria for the total transport (keyword: bdslpeffini = total) or the bed load transport only (keyword: bdslpeffini = bed) through ([Soulsby, 1997]):

In this equation is \(\psi\) the difference in angle between the flow direction and the on-slope directed vector, \(\beta\) the bed slope and \({\phi}_{i}\) the angle of repose.

[de Vet, 2014] provides a detailed overview on how the bed slope and flow direction are calculated and how the bed slope effect is combined with the dilatancy concept if the adjustment to the initiation of motion is considered.

It is also possible to prescribe a given bed slope. The result is that the swash zone profile is teased towards a given bermslope. This functionality Works in surfbeat mode (where H/h>1) and in stationary mode (where h<1m) and have been tested for profiles Praia de Faro (keyword: bermslope = desired slope).

In XBeach-G, bed slope effects on sediment transport are included by changing the effective Shields parameter \(theta'\) is modified according to [Fredsøe, 1992]:

where \(beta\) is the local angle of the bed, \(phi\) is the angle of repose of the sediment (approximately 30-40), and the right-hand term is less than 1 for up-slope transport, and greater than 1 for down-slope transport.

Bottom updating

See also

Bed updating is implemented in func:morphevolution/bed_update.

Due to sediment fluxes

Based on the gradients in the sediment transport the bed level changes according to:

In \(\rho\) is the porosity, \({f}_{mor}\) (keyword: morfac) is a morphological acceleration factor of O(1-10) ([Reniers et al., 2004]) and \({q}_{x}\) and \({q}_{y}\) represent the sediment transport rates in x- and y-direction respectively. Sediment transport can be activated with the keyword: sedtrans.

The morphological acceleration factor speeds up the morphological time scale relative to the hydrodynamic timescale. It means that if you have a simulation of 10 minutes with a morfac of 6 you effectively simulate the morphological evolution over one hour. There are now two ways in which you can input the time-varying parameters in combination with morfac:

All times are prescribed on input in morphological time. If you apply a morfac all input time series and other time parameters are divided internally by morfac. This is determined with keyword morfacopt = 1. If you now specify a morfac of 6, the model just runs for 10 (hydrodynamic) minutes each hour, during which the bottom changes per step are multiplied by a factor 6. This of course saves a factor of 6 in computation time.

This method is appropriate for short-term simulations with extreme events. This approach is only valid as long as the water level changes that are now accelerated by morfac do not modify the hydrodynamics too much. This is the case if the tide is perpendicular to the coast and the vertical variations do not lead to significant currents. If you have an alongshore tidal current, as is the case in shallow seas, you cannot apply this method because you would affect the inertia terms and thus modify the tidal currents.

Alternatively you run the model over, say, over a tidal cycle, and apply the morfac without modifying the time parameters. This means you leave all the hydrodynamic parameters unchanged and just exaggerate what happens within a tidal cycle. As long as the evolution over a single tidal cycle is limited, the mean evolution over a tidal cycle using a morfac is very similar to running morfac tidal cycles without morfac. See [Roelvink, 2006] for a more detailed description of this approach. This option is enabled with keyword: morfacopt = 0.

This method is more appropriate for longer-term simulations with not too extreme events.

Avalanching

To account for the slumping of sandy material from the dune face to the foreshore during storm-induced dune erosion avalanching (keyword: avalanching) is introduced to update the bed evolution. Avalanching is introduced via the use of a critical bed slope for both the dry and wet area (keyword: wetslp and dryslp). It is considered that inundated areas are much more prone to slumping and therefore two separate critical slopes for dry and wet points are used. The default values are 1 and 0.3 respectively. When this critical slope is exceeded, material is exchanged between the adjacent cells to the amount needed to bring the slope back to the critical slope.

To prevent the generation of large shockwaves due to sudden changes of the bottom level, bottom updating due to avalanching has been limited to a maximum speed, defined by a characteristic length and time scale. This speed is found by distributing the vertical change in bed level required to fulfill the criterium for the critical slope over the characteristic time scale (avaltime). This avaltime is proportional to the trep by the nTrepAvaltime parameter. Moreover, to remove grid size dependency, the bed level change is scaled with a ratio between the infragravity swash motion (following []) and the local grid size.

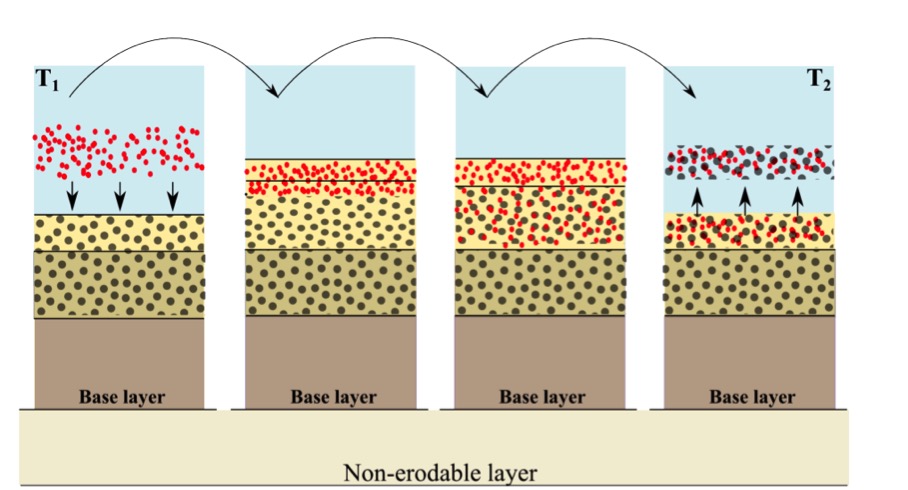

Bed composition

If the effect of different sediment fractions, sorting and armoring are of importance, a bed composition constituting multiple sediment fractions can be defined. Each sediment fraction is characterized by a median grain size (\({D}_{50}\)) and possible a \({D}_{15}\) and \({D}_{90}\) as well. When using multiple sediment fractions, multiple bed layers are needed as well to describe the vertical distribution of the sediment fractions in the bed.